— Flag of Spain Source: self-modification based on external source

- • Spanish Constitution of 1978

- • Law 39/1981, of October 28, regulating the use of the Flag of Spain and other flags and ensigns

- • Royal Decree 2335/1980, of October 10, regulating the use of the Flag of Spain and other flags and ensigns aboard national ships

- • Royal Decree 441/1981, of February 27, technically specifying the colors of the Flag of Spain

- • Partially, in what does not oppose the previous provisions, Royal Decree 1511/1977, of January 21, approving the Regulation of Flags and Standards, Guidons, Insignia and Distinctions.

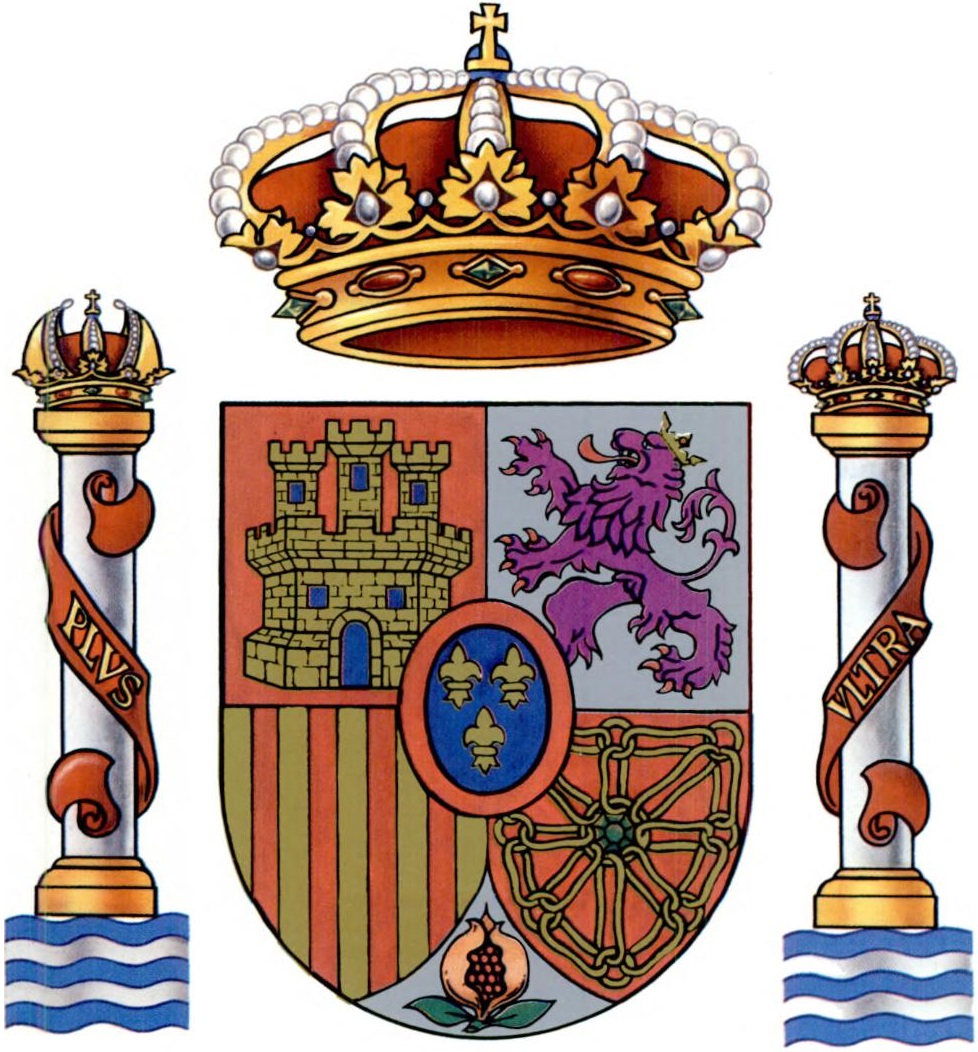

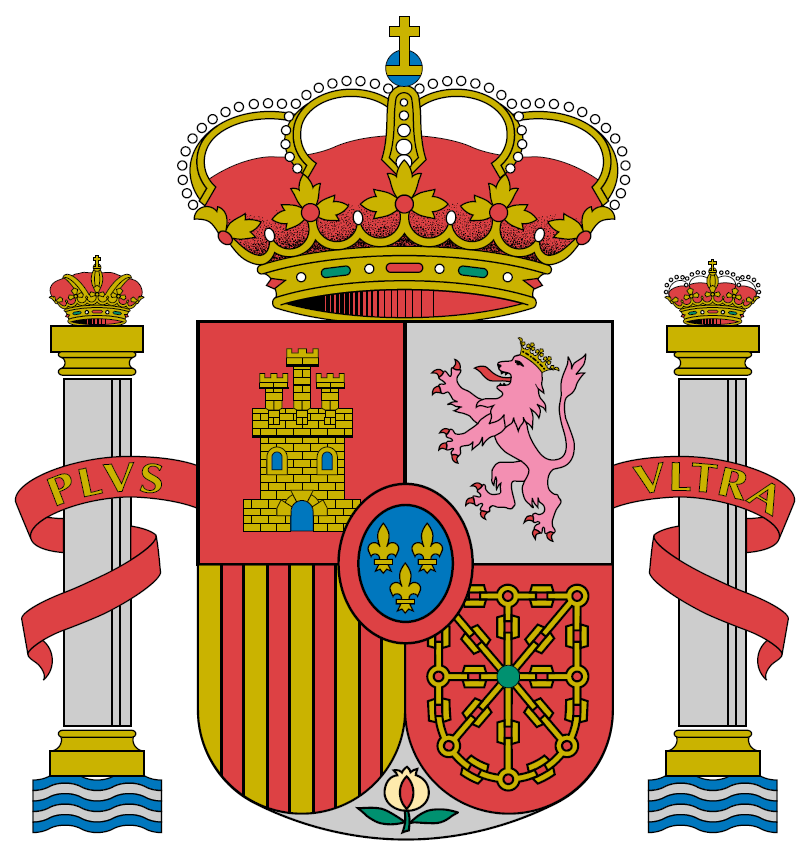

----------- - • Law 33/1981, of October 5, on the Coat of Arms of Spain

- • Royal Decree 2964/1981, of December 18, making public the official model of the Coat of Arms of Spain

- • Royal Decree 2267/1982, of September 3, technically specifying the colors of the Coat of Arms of Spain

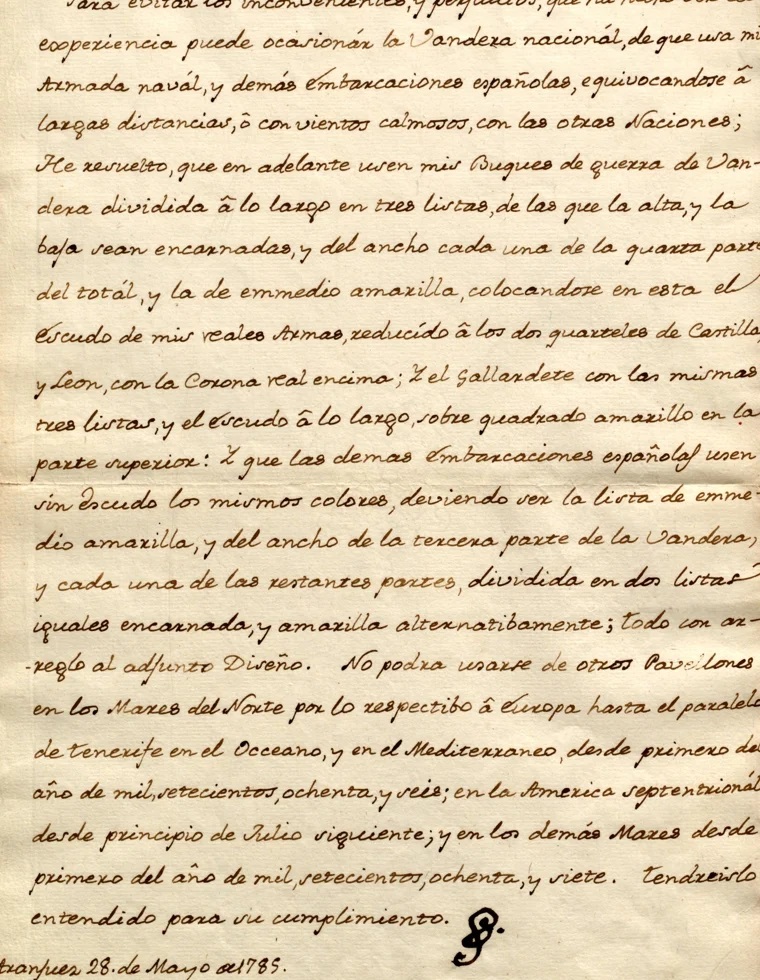

In accordance with the Spanish Constitution of 1978, the Flag of Spain consists of 3 horizontal stripes, red, yellow, and red, with the central one (the yellow one) being twice the width of each of the outer ones (the red ones). Historically, the central stripe bears the Coat of Arms of Spain.

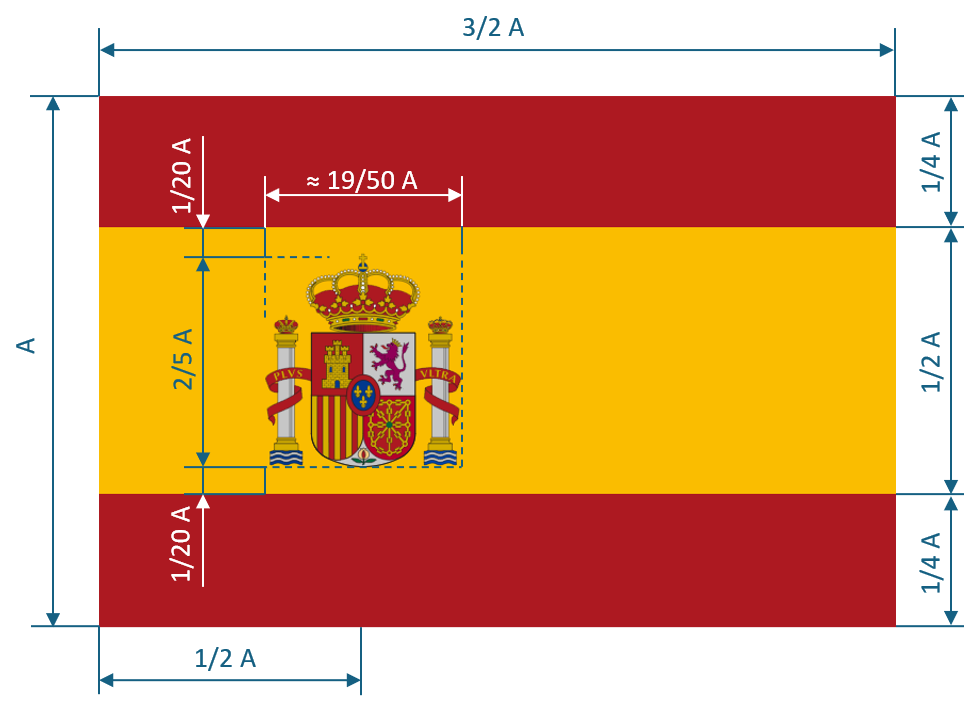

The Constitution's brief reference to the Flag of Spain is developed by Law 39/1981, of October 28. Regarding the flag's shape and geometry, this Law does not include any specifications; it is Royal Decree 2964/1981, of December 18, which, in addition to providing the official model of the Coat of Arms of Spain, partially develops it by specifying several aspects it leaves undefined. Thus, the norm establishes the «normal proportion» of the flag and associates it with a length-width ratio of 3:2, which indirectly equates to establishing that the standard shape of the flag is rectangular. In certain cases (flag variants regulated for specific cases), it may adopt a different shape (commonly, square).

The aforementioned Law 39/1981 introduces the possibility of incorporating the Coat of Arms of Spain into the yellow stripe, although without specifying how. Furthermore, it prescribes the inclusion of the emblem for certain specific cases covered by the norm, without preventing or prohibiting it in other different cases.

For its part, the aforementioned Royal Decree 2964/1981 specifies in its articles how the coat of arms must be incorporated into the central stripe of the flag: when the flag has a rectangular shape, the axis of the coat of arms will be placed at a distance, with respect to the mast, halyard, or sleeve, equivalent to 1/3 of the length of the flag or, what is the same, 1/2 of its width; in all other cases (square flags or those with other non-rectangular geometries), the coat of arms will be placed centrally.

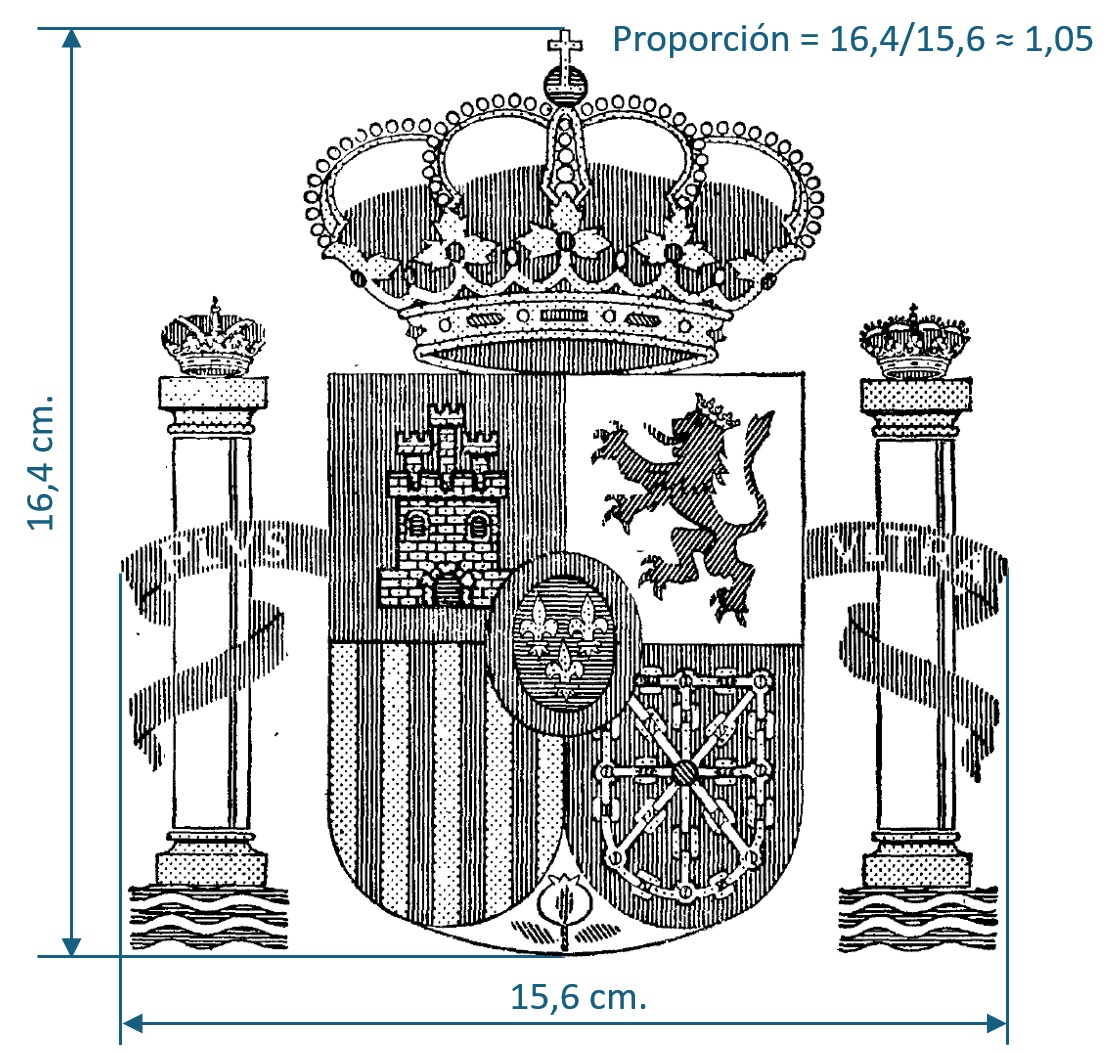

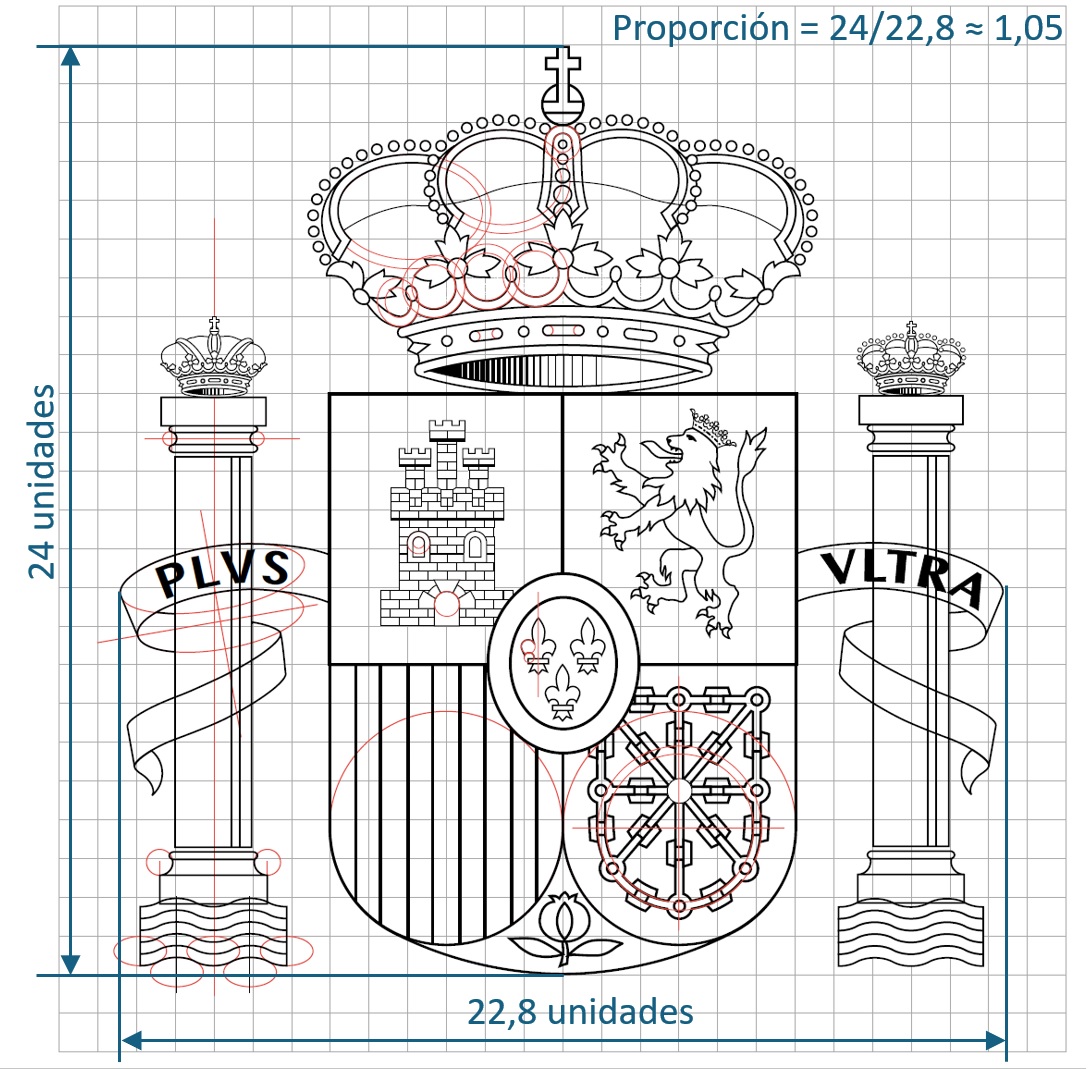

Regarding the dimensions of the coat of arms on the flag, the Royal Decree in question establishes that its height will be 2/5 (i.e., 40%) of the width of the ensign, although it leaves the corresponding value for the width undefined. However, the official model of the coat of arms is inserted in the first article of the norm, from which an approximate height-to-width ratio of 1.05 can be inferred. This proportion coincides with that deduced from a grid for the graphic construction of the coat of arms included in the Central Government Institutional Image Manual (which will be detailed further in later paragraphs). Therefore, starting from this data and operating appropriately, it can be established that the width of the coat of arms will be approximately 19/50 of the width of the ensign.

Traditionally, the Flag of Spain has incorporated the coat of arms in its central stripe, among other reasons, because it was conceived as a naval flag at its inception (in fact, this stripe was widened in the initial design, precisely, to give prominence to the coat of arms and reinforce its symbolism). Furthermore, over time, the perception of the coat of arms transcended the mere role of state ornament, becoming, as a representative symbol of the union of territories that gave rise to Spain, a substantial part of the common identity and, therefore, of the flag that symbolizes it.

Nevertheless, the flag has also been (and is) used without the emblem, sometimes as a kind of simplified flag, because its production or representation is more economical and simple, or, in past periods, because it had been expressly regulated in some specific area (see what was related above about the merchant marine). This variant of the flag is sometimes called the civil flag, in contrast to the variant with the coat of arms, sometimes called the state or institutional flag. Such concepts (apart from being used informally or colloquially) do not exist legally, since neither the Constitution nor any other legal provision formally contemplates or defines them, unlike what happens in other states; for example, Finland, whose current law on the matter expressly defines the Kansallislippu and the Valtiolippu, or Peru, which explicitly defines by law its national flag, without the coat of arms, distinguishing it from the war flag, with the coat of arms. Therefore, strictly speaking, in the Spanish legal corpus there is only the Flag of Spain, whose definition, as already emphasized, is given both by the Constitution and by the subsequent regulatory development on the matter.

Delving into the origin of this apparent dichotomy regarding the use of the coat of arms on the flag, it is worth noting that, according to certain authors, in the 1978 Constitution there was a «deliberate intention not to refer to other national symbols such as the anthem, the coat of arms or mottos, after a dictatorship characterized by the constant and abusive exaltation of those». Josu de Miguel Bárcena - Símbolos, neutralidad e integración constitucional. That is, according to these postulates, the constituents would have limited themselves to including a basic description of the flag to avoid divisions or compromising the achievement of consensus in the elaboration of the final text of the Magna Carta, avoiding the incorporation into the ensign of a coat of arms, whose latest official version, although it was approved by the government of Adolfo Suárez already in the stage of transition to democracy, still evoked the Franco regime, given the minimal differences with respect to the coat of arms used during that period.

Once the Constitution had entered into force, the normalization or settlement of the democratic regime was neither immediate nor exempt from complications; neither was it in relation to national symbols, since, as certain authors point out, «for several years, the new political system was forced to coexist with a situation of provisionality, in which it was not entirely clear whether the official symbols were exactly the ones inherited from Francoism or not» Javier Moreno Luzón y Xosé M. Núñez Seixas - Los colores de la patria. Símbolos nacionales en la España contemporánea. This ambiguity became especially evident in the use of the coat of arms on the flag: in those early stages, it was not clear whether the constitutional flag lacked it, or if the latest official version, already referred to in the previous paragraph, should be used, especially since its public exhibition could be pointed out as a sign of connection with the Francoist regime or inclination towards the far right.

All this burgeoning bureaucratic and legislative framework, with its slow progress in rolling out the new constitutional symbols, as well as the particularly tense political and social context of the time, led to the use of the flag without the coat of arms becoming widespread to a certain extent, both institutionally and among the civilian population, during the early years of democracy. As previously noted, it was not until late 1981 that a new version of the coat of arms of Spain (the current one) was established as a clear symbol of the break with the dictatorial past, and Article 4 of the Constitution was legally developed, thus completing the definition of the flag by adding the coat of arms with the aforementioned characteristics. From then on, the complete variant of the flag (i.e., bearing the coat of arms in its central stripe) gradually became established until it became, de facto, the usual formal representation of the flag of Spain, recognized both nationally and internationally.

The colors of the stripes on the Spanish flag are technically specified in Royal Decree 441/1981, of February 27. The following table shows the colors defined in the standard for the CIELAB and CIE-1931 systems. The table includes an additional column with the equivalence to sRGB values (not included in the aforementioned Royal Decree), obtained from those corresponding to CIE-1931 under illuminant C:

| Color | Color designation | CIELAB | CIE-1931 | sRGB | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hue H* | Chroma C* | Lightness L* | Y | x | y | |||

| Red | Flag red | 35 º | 70 | 37 | 9,5 | 0,614 | 0,320 | (173, 25, 33) |

| Yellow | Flag golden yellow | 85 º | 95 | 80 | 56,7 | 0,486 | 0,469 | (250, 189, 0) |

- Conversion of the original chromaticity coordinates (Yxy) to tristimulus values (XYZ).

- Adaptation of values obtained in 1. to illuminant D65, using the Bradford transformation.

- Conversion of the values obtained in 2. to linear sRGB.

- Gamma correction of the linear values obtained in 3.

Regarding the colors of the coat of arms, the following table shows the values extracted from the Royal Decree 2267/1982, of September 3, as well as the equivalence to sRGB values (not included in the said Royal Decree) from those corresponding to CIE-1931 under illuminant C:

| Color | Color designation | CIELAB | CIE-1931 | sRGB | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hue H* | Chroma C* | Lightness L* | Y | x | y | |||

| Sinople | Flag green | 165.0 | 41.0 | 31.0 | 6.7 | 0.223 | 0.438 | (0, 104, 56) |

| Azur | Flag blue | 270.0 | 35.0 | 26.0 | 4.7 | 0.168 | 0.171 | (0, 56, 142) |

| Oro | Flag gold | 90.0 | 37.0 | 70.0 | 40.7 | 0.395 | 0.403 | (212, 175, 0) |

| Plata | Flag silver | 255.0 | 3.0 | 78.0 | 53.2 | 0.303 | 0.311 | (198, 198, 198) |

| Sable | Flag black | – | 0.0 | 10.0 | 1.1 | 0.310 | 0.316 | (26, 26, 26) |

| Gules | Flag red | 35.0 | 70.0 | 37.0 | 9.5 | 0.614 | 0.320 | (173, 25, 33) |

| Púrpura | Flag purpure | 0.0 | 52.0 | 50.0 | 18.42 | 0.426 | 0.263 | (143, 0, 87) |

On the other hand, in 1999 a norm was approved for the homogenization of the institutional image of the Central Government Administration (or CGA), through Royal Decree 1465/1999, of September 17, which resulted in an Institutional Image Manual with design guidelines for printed material, stationery, folders, brochures, publications, magazines, posters, signage, plaques, cards, banners, etc., etc. This institutional image revolves around the Spanish coat of arms, which is why the manual proceeds to systematize its graphic construction. For the form and representation of this element, the manual is based on the heraldic description of the coat of arms made in Law 33/1981 and, mainly, on the official model included in Royal Decree 2964/1981. However, the manual omits Royal Decree 2267/1982 and proceeds to define, apart from the officials, colors that it names as institutional colors, in the Pantone, four-color process (CMYK) and RGB systems.

Some years later, when the use of the internet had become widespread, a Digital communication guide for the Central Government Administration was published, divided into two fascicles, as a framework of recommendations and good practices for the design of websites, portals, and electronic headquarters belonging to said administration. The second of these fascicles addresses the graphic issues aimed at providing or transmitting the officiality of the designed web spaces, which is why we find references to the use of the Spanish coat of arms, whose colors are specified to coincide with those of the CGA manual, as well as the Spanish flag and the European Union flag. In the case of the Spanish flag (specifically, its stripes), the guide disregards the official colors specified in Royal Decree 441/1981 and defines its own colors, in the RGB and four-color process (CMYK) systems.

For the flag stripes, the guide defines their colors as follows:

| Color | RGB | Four color (CMYK) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R | G | B | Cyan | Magenta | Yellow | Black | |

| Red | 173 | 21 | 25 | 0% | 88% | 86% | 32% |

| Golden yellow | 250 | 189 | 0 | 0% | 24% | 100% | 2% |

Regarding the coat of arms, both the manual and the guide define its colors as follows:

| Color | Pantone | RGB | Four color (CMYK) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Código | R | G | B | Cyan | Magenta | Yellow | Black | |

| Black | - | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0% | 0% | 0% | 100% |

| Red | 186 | 181 | 0 | 39 | 0% | 100% | 80% | 0% |

| Silver | 877 | 178 | 178 | 178 | 0% | 0% | 0% | 30% |

| Gold | 872 | 159 | 126 | 0 | 20% | 30% | 100% | 0% |

| Green | 3415 | 0 | 111 | 70 | 100% | 10% | 70% | 0% |

| Blue | 2935 | 0 | 68 | 173 | 100% | 50% | 0% | 0% |

| Purpure | 218 | 216 | 90 | 174 | 0% | 70% | 0% | 0% |

| Pomegranate | 1345 | 246 | 203 | 126 | 0% | 10% | 40% | 0% |

Next, a comparison of the official colors with those of the CGA manual and guide is shown:

| Element | Color | sRGB according to Royal Decrees | sRGB according to manual and/or guide | Difference ΔE (*) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flag stripes | Flag red | (173, 25, 33) | (173, 21, 25) | 2,3 |

| Flag golden yellow | (250, 189, 0) | (250, 189, 0) | 0 | |

| Flag coat of arms | Sinople (green) | (0, 104, 56) | (0, 111, 70) | 5,1 |

| Azur (blue) | (0, 56, 142) | (0, 68, 173) | 9,4 | |

| Gold | (212, 175, 0) | (159, 126, 0) | 13,9 | |

| Silver | (198, 198, 198) | (178, 178, 178) | 7,9 | |

| Sable (black) | (26, 26, 26) | (0, 0, 0) | 10,8 | |

| Gules (red) | (173, 25, 33) | (181, 0, 39) | 8,7 | |

| Purpure | (143, 0, 87) | (216, 90, 174) | 39,5 | |

| Pomegranate | Not defined | (246, 203, 126) | N/A |

| ΔE < 1,0 | Imperceptible difference to the human eye |

| 1,0 ≤ ΔE < 2,0 | Minimally perceptible difference, only by experts |

| 2,0 ≤ ΔE < 3,5 | Small difference |

| 3,5 ≤ ΔE < 5,0 | Medium difference, clearly perceptible |

| 5 ≤ ΔE < 10,0 | Large difference, clearly different colors |

| ΔE ≥ 10,0 | Very obvious or noticeable difference |

In addition to the digital representation, in the material world there are also noticeable divergences in the coloring of the flag; particularly in the central stripe, whose color, in a significant percentage of cases, differs notably from the official one, with a whole palette of possible yellows being observed. The same occurs with the lion on the coat of arms, whose hue (red, dark violet, pink) does not seem to hit the mark with the standard.

— Example 1 Spanish flag color disparity Source

— Example 2 Spanish flag color disparity Source

— Example 3 Spanish flag color disparity Source

Generally, following the prevailing practice, the flag is made of 100% run-resistant, satin polyester with a weight of at least 110 g/m2, featuring a double hem and double perimeter stitching, as well as a sleeve or reinforcement tape 5 cm wide on the side of the mast, with two metal eyelets or rings for fastening. Its coat of arms is added via stamping with 100% penetration (total color transfer and visibility on both sides) using heat-set dyes of maximum fastness.

On certain occasions, especially indoors or at events that require greater ceremoniousness, the flag is made of satin fabric (silk or nylon), or silk taffeta, in both cases double-sided, with a weight that can range between 160 and 350 g/m2; and an embroidered coat of arms using silk threads, as well as gold and silver, with a three-dimensional or relief effect.

○ Reverse of the flag

Although the current legislation does not explicitly define the reverse of the flag, it does mention, through the previously cited Royal Decree 2964/1981, that the coat of arms «shall appear on both sides», which, indirectly, confirms that a reverse of the flag exists as such. However, it leaves undefined how the coat of arms must appear, that is, whether it should be represented in a natural way (without a mirror effect) or whether it should appear inverted. In the latter case, the representation of the flag's reverse would be the result of rotating it 180° with respect to a vertical axis of rotation, obtaining a mirror image of the obverse. Nevertheless, heraldic orthodoxy suggests that a coat of arms must always be presented in its correct form, thus respecting the intrinsic nature of the emblem, regardless of the side or viewpoint from which it is observed. This, combined with a literal interpretation of the aforementioned rule (which states «the coat of arms of Spain (...) shall appear on both sides», without introducing any other nuance), leads to the conclusion that the representation of the flag's reverse must maintain the coat of arms without inverting it.

There is a third position that advocates representing the reverse of the flag in an inverted manner but making the coat of arms' motto legible without changing the physical location of the words relative to the obverse. That is to say, instead of PLUS ULTRA, it would read ULTRA PLUS. This solution, although it may have some heraldic basis, distorts the meaning of the motto, and would therefore be tantamount to arbitrarily altering a specific color or symbol of the coat of arms.

○ Vertical flag

It must first be established that, in the field of vexillology, the part, color, or emblem with the greatest symbolism is usually considered the point or area of honor of a flag. This point or area must always remain, regardless of the display arrangement adopted by the flag, in the upper part (or upper left, as the case may be) from the observer's perspective. For example, on the United States flag, the point of honor is the canton, so, according to its sectoral regulations, when the flag is displayed vertically (statically), the said canton must remain in the upper left part, meaning it would not be a matter of simply rotating the flag 90º from a horizontal position, but it must also be flipped so that the canton is in the required position. With respect to Spain, the legislation does not expressly define the configuration to be adopted for a vertical format of the flag nor what its point or area of honor is, although it can be tacitly assumed, by analogy with the general vexillological criteria mentioned above, that it is the coat of arms. Therefore, the vertical display of the Spanish flag can adopt two solutions: one would be the result of a simple rotation of 90º clockwise, whereby the coat of arms would remain in the upper part; another, more correct and orthodox, would consist of repeating the same rotation operation described, with the exception of the coat of arms, which would maintain its correct orientation from the observer's point of view (i.e., the coat of arms does not rotate), thus respecting its intrinsic nature, as mentioned in the previous section. This latter solution has the disadvantage of requiring flags with this format to be expressly manufactured or supplied, whereas the former can be adopted with a standard flag.

According to the Album des pavillons nationaux et marques distinctives, for the case of the Spanish flag, the use corresponds to

| Private | Governmental Non-Military | Governmental Military | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Land use | |||

| Maritime use |

Each cell, as the intersection of a specific row and column, will correspond to a concrete situation for the flag's use (for example, land use by private citizens). The cells would be completed with a symbol ⬤ or when a certain combination is valid or permitted for a given flag. Normally, to simplify the representation, since the use of the table is standardized and widespread, the descriptive texts are omitted and only the inner cells are represented, resulting in a type of grid or chart like this

When handling or using the Spanish flag, a series of rules conventionally accepted in the vexillological and protocol field are applied, also known as flag etiquette or good practices; namely:

- The raising and lowering of the flag must be done in time with the national anthem, if it is being played, or, in any case, in a ceremonial manner.

- The flag should be raised at sunrise and lowered at sunset, unless the location is adequately illuminated during the night.

- The flag must always fly at the top of the flagpole, with the halyard or rope firmly secured so that it can fly freely and without restriction.

- The flag must be well secured, preventing it from falling or collapsing.

- When the flag is located outdoors, it should be taken down in case of strong winds exceeding 60 km/h or, if installed on a flagpole, be lowered and secured to it.

- The flag must never touch the ground.

- If the flag is visibly deteriorated, it must be replaced with a new one.

In accordance with the provisions of Law 39/1981, when flying with other flags, the Spanish flag must always occupy a prominent, visible, and place of maximum honor, and the others cannot be larger than the rojigualda. If the number of flags is odd, the Spanish flag must be placed in the central position; if the number is even, of the two central positions, the Spanish flag will be located to the observer's left.

— Placement of the Spanish Flag with an odd number of flags Source

— Placement of the Spanish Flag with an even number of flags Source

When flags of companies, private entities, etc. exist (for example, in a hotel), they must be kept separate from institutional flags (that is, they should not be part of that group of flags).

When international flags are present, they must all be the same size and will generally be placed in alphabetical order according to the language of the host country, entity, or organization, with the flag of the host country, entity, or organization potentially occupying a prevalent position. On occasion (as occurs, for example, in the European Union), flags are arranged in alphabetical order using the name of the country in its own official language.

In bilateral meetings, the host's flag is placed on the right of the podium or meeting place (to the audience's left) and the guest's flag is placed on the left (to the audience's right). This rule applies to both standing flagpoles and tabletop flags.

Flags in official, institutional, or similar events must be in perfect condition (clean, without wrinkles or tears). Those that bear an emblem or coat of arms (like Spain's), as this is considered the point or area of honor, must be presented in a way that shows it clearly and prominently. Concealment or incorrect orientation of the coat of arms is considered a lack of respect and/or a serious protocol error.

— Incorrect Placement of the Spanish Flag (partially concealed Coat of Arms) Source

— Incorrect Placement of the Spanish Flag (placed upside down) Source

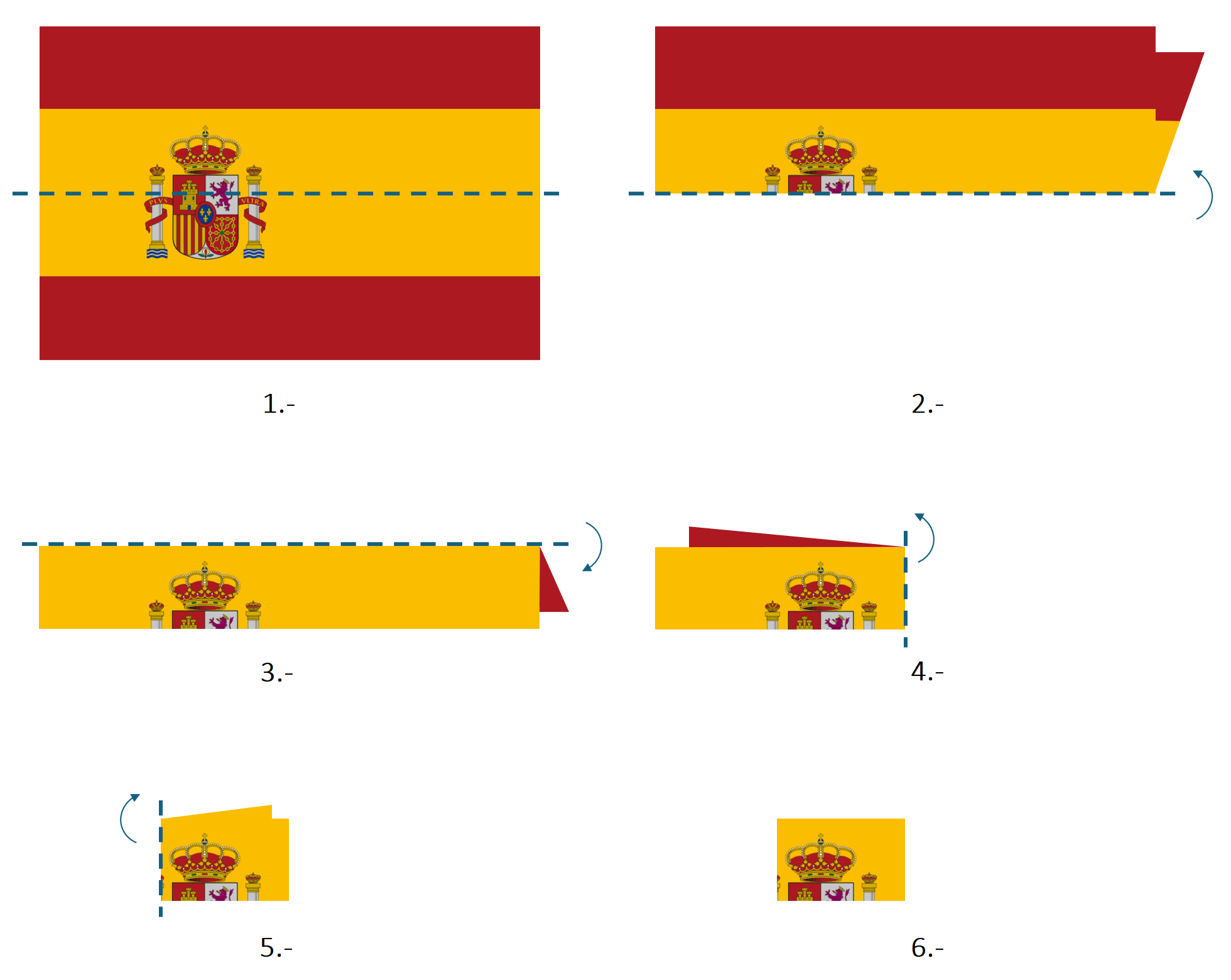

Regarding the folding of the flag, although there are different procedures depending on the specific case (lowering, funeral honors, etc.), it is usually carried out in such a way that the flag remains presented with the coat of arms visible.

With the establishment of the Bourbon dynasty in Spain through Philip V, the royal symbol became composed of the royal arms on white cloth. White was the dynastic color of the Bourbons, which is why, in the various territories ruled by this family (France, Parma, Sicily and Naples, in addition to Spain), a cloth of that color was used. This fact made it difficult to distinguish the respective national flags of ships, which is why, at some point (probably after some fatal mistake), a change in the flag of Spain's warships began to be considered. This is suggested by the fact that, during the reign of Ferdinand VI, in article I of Title III of the Third Treaty, of the Ordinances of His Majesty for the military, political and economic government of his Naval Armada, from 1748, it was established that «For now, all ships of the Armada shall use the ordinary national white flag with the coat of my arms, until I see fit to dispose otherwise. And, in the meantime, they shall not fly another except on occasions when it is permitted according to maritime custom.»

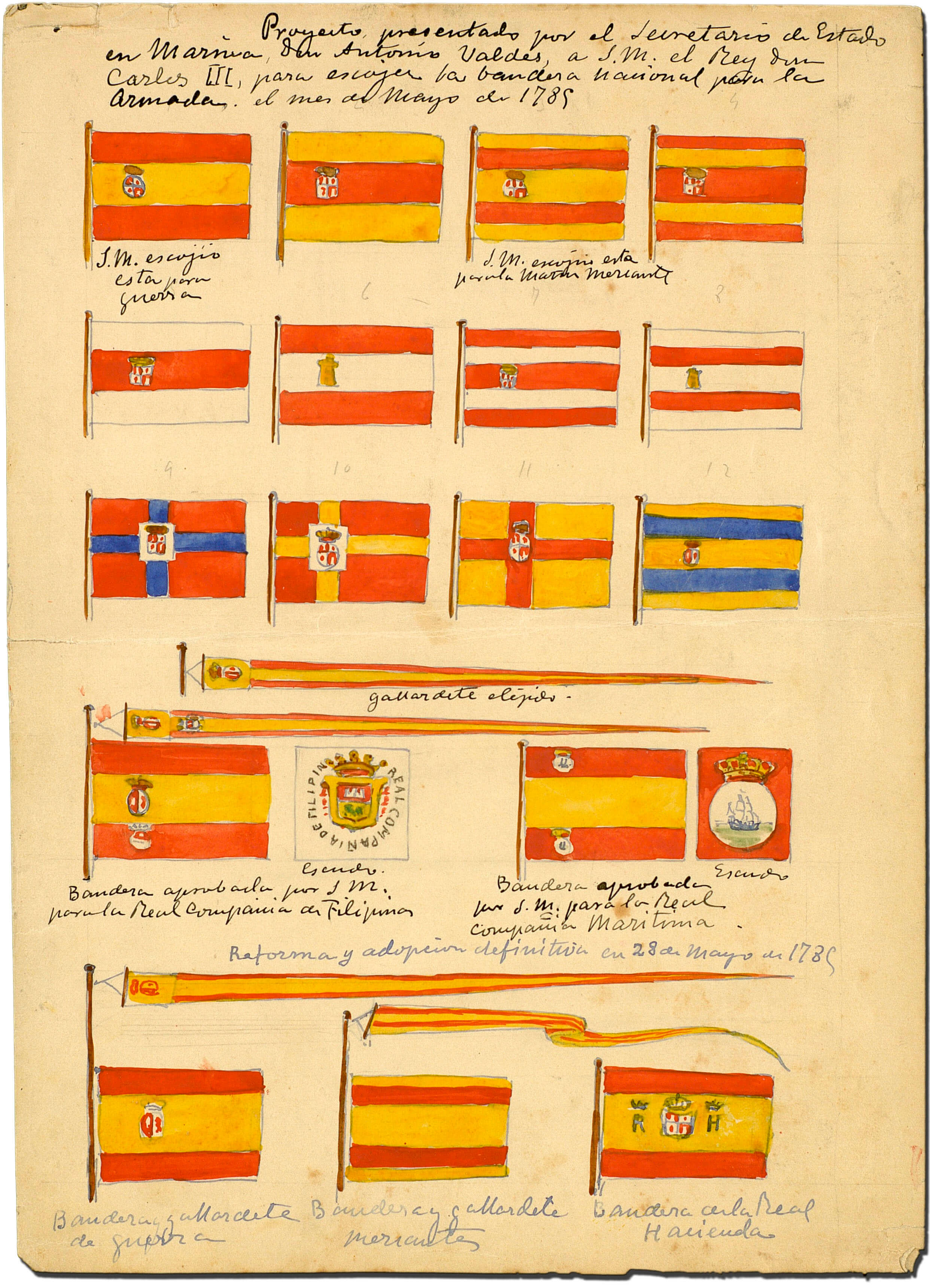

Already during the reign of Charles III, the monarch commissioned Antonio Valdés y Fernández Bazán, then Secretary of State and Universal Office of the Navy, to design a new flag for the Armada, one that was easily identifiable—that is, one that would not be confused with the sails, would be distinguishable from the colors of the sky and the sea, would be noticeable in unfavorable weather, and would not be confused with those of other nations.

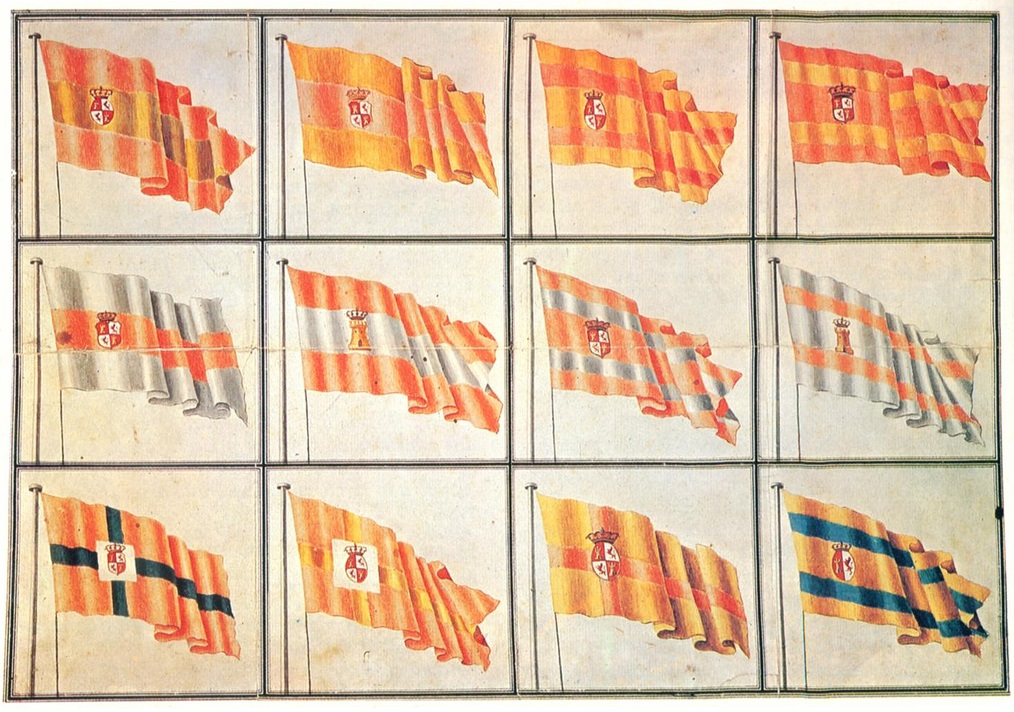

Valdés's cabinet prepared a project with twelve different proposals. In the plate on which they were captured, the flags were grouped into three rows of four flags each, presenting different combinations of colors and coat of arms formats. In the first row, the proposals featured horizontal stripes (a common format at the time for naval flags) and used red and yellow as colors, with a quartered coat of arms. In the second row, the flags were identical to those in the first, but substituting red for white and yellow for red, and introducing a coat of arms reduced solely to a castle in a couple of models. In the third, cruciform versions of the flags predominated, blue was introduced in some, and one in particular presented a parted coat of arms.

— Plate with the proposals for the flag reform project Source

— Subsequent reproduction of Valdés' proposals Source

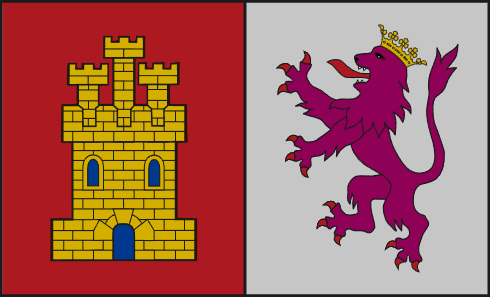

From among the proposals drafted, the monarch selected the first one—that is, the one that featured three horizontal stripes of color, respectively, red, yellow, and red—although he ordered a modification to the central stripe, which was made double the width of the upper and lower stripes, so that the coat of arms could be larger. For this same purpose, the coat of arms, initially quartered, was replaced by the parted one from the twelfth proposal, which featured only the quarters of Castile and León, in a circle or oval. Furthermore, the coat of arms was positioned shifted toward the mast or halyard (not centered horizontally in the central stripe) to facilitate its identification and visibility when the flag was not fully unfurled.

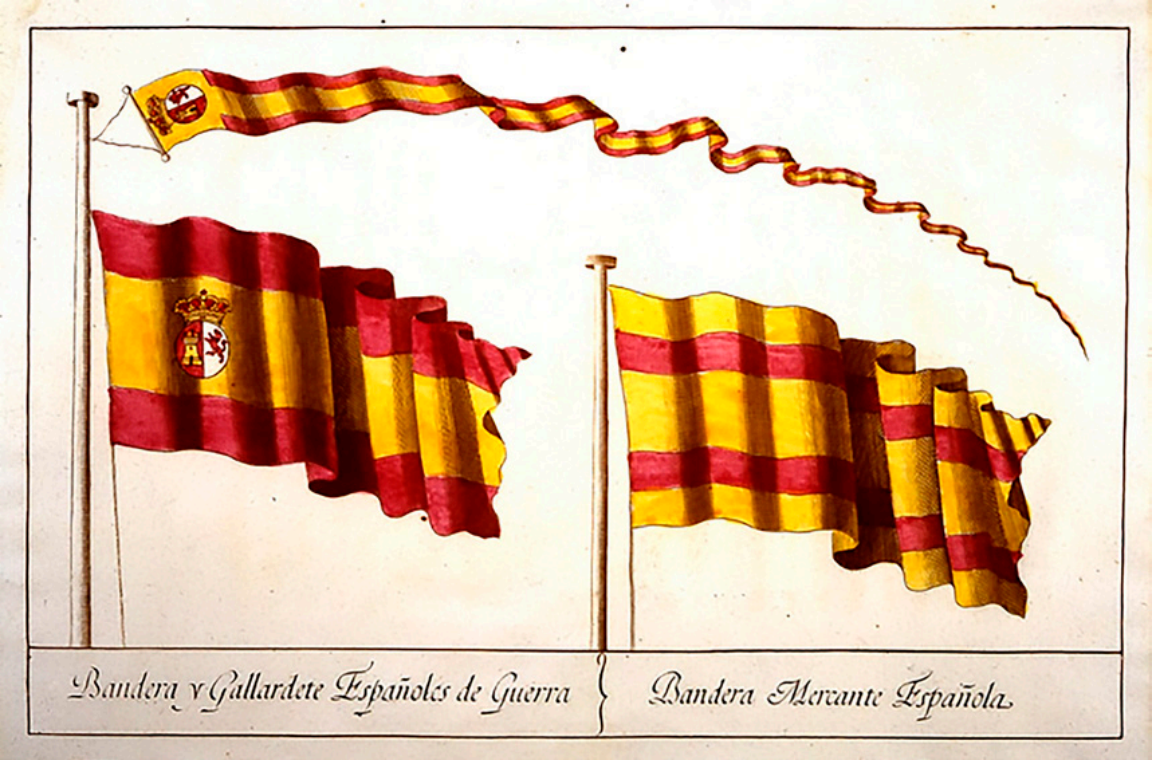

Finally, by means of the Royal Decree of May 28, 1785, Charles III stipulated a new war flag: «To avoid the inconveniences and losses that experience has shown can be caused by the national Flag used by my naval Armada, and other Spanish Vessels, by being mistaken at long distances, or with calm winds, for those of other Nations; I have resolved that henceforth my War Ships shall use a Flag divided lengthwise into three stripes, of which the high and the low ones shall be red, and the width of each one shall be a quarter part of the total, and the middle one yellow, placing thereon the Coat of my Royal Arms reduced to the two quarters of Castile and León with the Royal Crown on top; and the Pennant with the same three stripes, and the Coat of Arms along its length, on a yellow square in the upper part: And the other Vessels shall use, without the Coat of Arms, the same colors, the middle stripe being yellow, and the width of the third part of the Flag, and each of the remaining parts divided into two equal alternating stripes of red and yellow, all in accordance with the attached design. No other ensigns may be used in the Northern Seas with respect to Europe up to the parallel of Tenerife in the Ocean, and in the Mediterranean from the first of the year one thousand seven hundred and eighty-six: in North America from the beginning of the following July; and in the other Seas from the first of the year one thousand seven hundred and eighty-seven. You will understand this for its compliance. Signed by the hand of H.M. in Aranjuez on the twenty-eighth of May of one thousand seven hundred and eighty-five. To D. Antonio Valdés.»

— Spain's War Flag and Pennant, as well as Merchant Flag (1785) Source: Archivo Histórico de la Armada

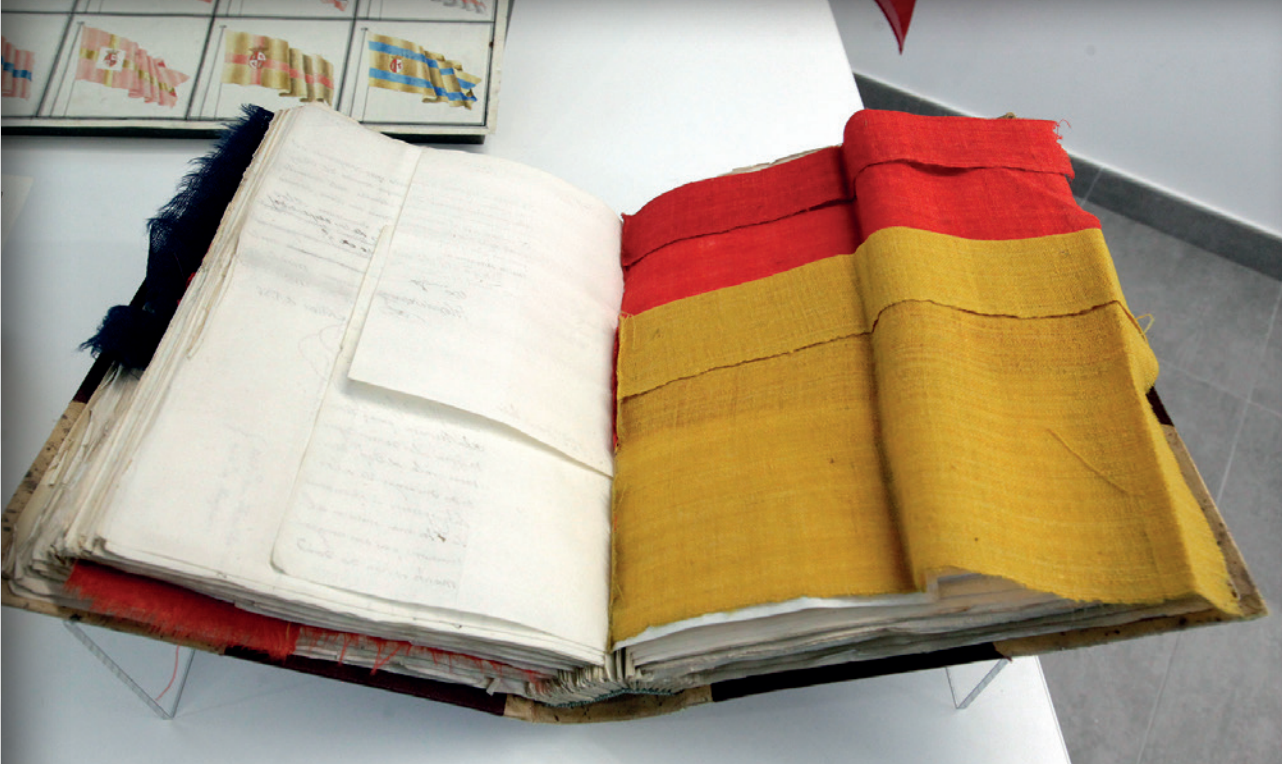

— Flag Dossier, with wool samples for its manufacture Source

From reading the Ordinances of Ferdinand VI, of 1748, and the Royal Decree of Charles III, of 1785, it is clear that, even back then (and it is deduced that previously), there existed a concept of the national identity, insofar as the flags used by the Navy are referred to by that name («national flag»), although it should be noted that the national concept must be understood, in terms of its political-legal connotations, from the perspective of the era in question, without being mimetically comparable to the one that may exist today. In any case, it is clear that the rojigualda flag, in addition to a functional origin (avoiding confusion and mistakes at sea), a naval origin (it is used by the Navy) and a military origin (it is the war flag), was created, if not with the strict consideration, then with the imprimatur of a national flag, by virtue of the already established concept of extraterritoriality enjoyed by Navy ships.

Aside from the adoption of the new flag due to the need to avoid inconveniences and losses at sea, as argued by the Royal Decree, certain authors maintain that this action would also aim to achieve a second objective not expressly stated in the rule, which would be to create distance with respect to other Bourbon kingdoms, by discarding the dynastic white color from the national flag; particularly, with France, with which disagreements and clashes had been occurring, often harming Spain's interests: «Spain was interested in distancing itself from that abusive and compromising relationship from which it gained little benefit. One of the means to achieve this goal was to differentiate, beyond any doubt, the warships and commercial vessels of both kingdoms; a distancing that had to be carried out with prudence and caution. A subterfuge was enough to camouflage the real reason for the flag change so that, from its entry into force, the new naval, war, and merchant flag would show a patent difference from those of neighboring France in a politically correct way.» José Luis Ruiz de la Hermosa, Jesús Dolado Esteban, Eduardo Robles Esteban - La bandera que nació en la mar

In relation to the design of the flag, there are authors who consider that its configuration, based on red and yellow stripes with the coat of arms, obeys a fusion of the symbology of the kingdoms that originally formed Spain, thus resulting in a common national symbol: «Thus the naval ensign is born as a symbol of the original union in a combination of colors and coat of arms in which the former are Aragonese, the latter Castilian, and the whole is Spanish.» Hugo O'Donell - Excerpt from ABC of the work Símbolos de España. In fact, other precedents already materialized «the idea of gathering in a single flag the symbols—charges or colors—of the kingdoms that formed the superior national entity» Hugo O'Donell - Orígenes y trayectoria naval de la bandera de España, as happened in 1707 with the Union Flag (or Union Jack) of Great Britain following the union of the crowns of Scotland and England. Other authors, however, consider that in the conception of the new naval flag there would not be such an intention, but that it would be due to the influence of the most abundant colors (gules and gold) in the heraldry of the historical Spanish kingdoms.

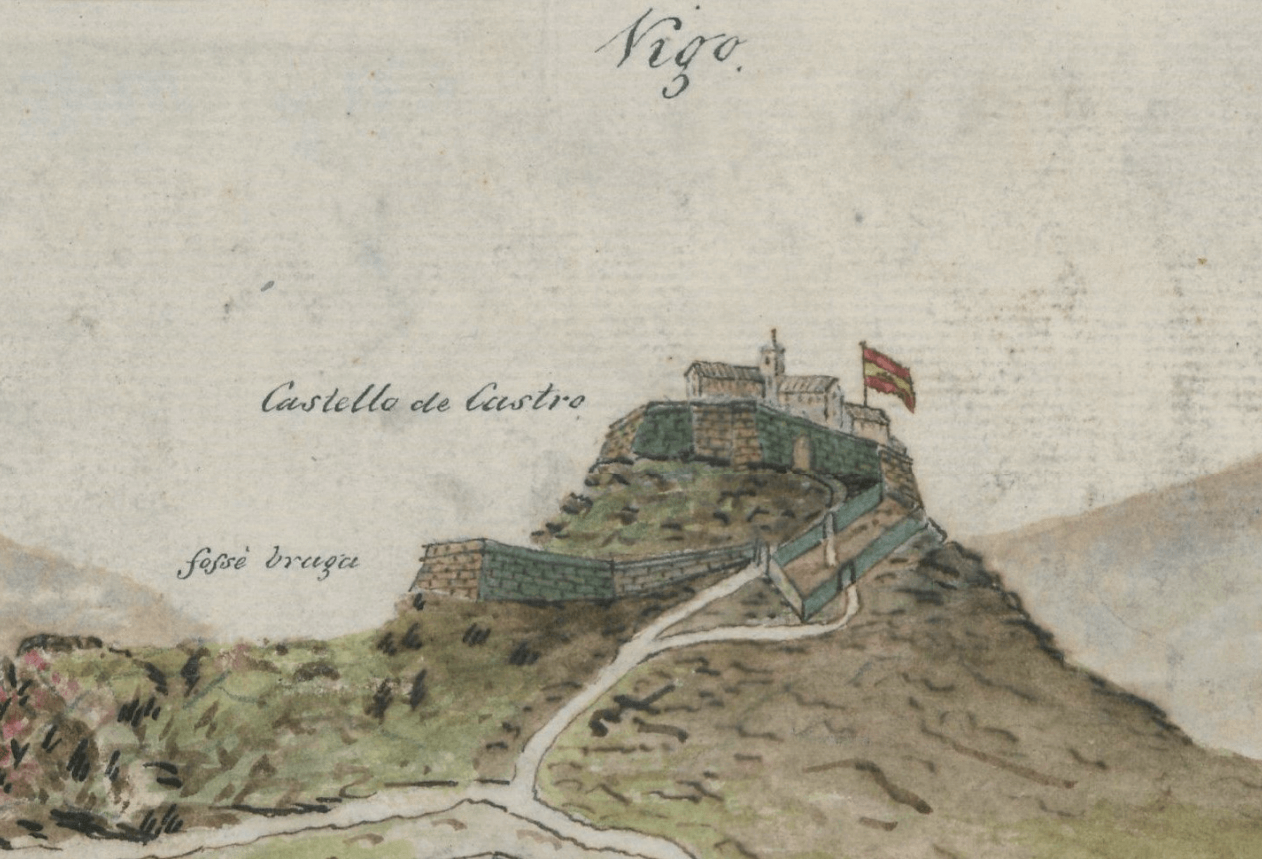

Somewhat later, in 1793, through the General Ordinances of the Naval Armada, Charles IV ordered that, in addition to ships, the national flag should also fly in maritime posts, on their castles or any others along the coasts, as well as in naval arsenals, shipyards, and barracks. This fact began to promote and generalize the association of the flag with the territory, surpassing its original conception as a war flag, that is, «on the coasts and on the land borders, the same red-yellow-red flag was raised which now said in a general way and adequately interpreted by all, Spaniards and foreigners: “the territory of Spain begins here”». Antonio Manzano Lahoz - El triple camino de la bandera nacional

After the Napoleonic invasion and the subsequent Peninsular War, a patriotic or national identity sentiment arose in the population that used the rojigualda flag as a symbol of resistance and of differentiation against the invader. Later, when the Cortes of Cádiz promulgated the Constitution of 1812, by which sovereignty came to reside in the nation, the rojigualda flag, as the already predominant representative symbol, was, de facto, the flag of that new liberal nation.

— Castle of N.ª Sra. del Castro, in Vigo, about 2 weeks after the town was reconquered from Napoleonic troops (1810) Source

— Constitutional Cortes of Cádiz (1812) Source

Already in 1843, through the Decree of October 13 published in the Gazeta de Madrid, the Ministry of War of the Provisional Government of Joaquín María López ordered the unification of all flags and standards of the armed forces, given the differences between the war flag (that is, the one used by the Navy) and those specific to the Army corps. This decree, known as the unification decree, and the date of its publication, have been erroneously taken or cited in countless occasions and media as the moment when the rojigualda was officially declared the national flag of Spain, when, from a simple reading of the decree, it is clear that no such assertion exists, without thereby diminishing the noteworthy fact that the flag (with certain exceptions) officially became the same throughout the entire military establishment.

— Models of the new flag, standard, and cockade for the Army, according to the Decree of October 13, 1843, and subsequent partial modification by Royal Decree of December 28 Source

With the arrival of the First Republic, the flag continued to be the same, with the exception of the elimination of the royal crown on the coat of arms.

Following the Bourbon restoration, in January 1908, a Royal Decree ordered that on national holidays, the Spanish flag should fly on all public buildings, both civil and military, as well as in Provincial Councils, Town Halls, and official Corporations. A few years later, during the Dictatorship of Primo de Rivera, the aforementioned Royal Decree of July 19, 1927, stipulated that the merchant marine should use the same ensign as the war ensign but without the coat of arms, suppressing the old five-stripe ensign.

With the establishment of the Second Republic, the tricolor flag was established as the national symbol, whose stripes were made of equal width, the lower one being dark purple. As for the Spanish coat of arms, it adopted the form that appeared on the reverse of the five-peseta coins minted by the provisional government in 1869 and 1870, and it came to occupy the central position on the yellow stripe.

Following the outbreak of the Civil War, the rebel faction adopted the rojigualda flag, though it omitted references to the coat of arms, so it would be understood that the one used during the Second Republic remained in effect. Less than two years later, the coat of arms was modified, adopting much of the symbolism (quartered, Eagle of St. John) from that of the Catholic Monarchs. Subsequently, in 1945, the coat of arms was slightly redesigned.

Already during the pre-democratic period, in 1977, Adolfo Suárez maintained the flag, although he carried out a very minor redesign of the 1945 coat of arms. Certain authors describe this change as a botch job, typical of Suárez's strategy during the transition, who «made reforms without modifying the essentials so as not to irritate the Army; he changed symbols without changing them, an exercise in political tightrope walking to stitch together the transition to democracy (...) His fear of the regime's nostalgics, from which he himself originated, meant he did not dare to completely replace the coat of arms» Luis Miguel Sánchez Tostado - El desconocido escudo de la transición y “el gatopardo”].

In a country where the national sentiment is viewed with little enthusiasm, if not disdain, the flag is, among those considered national symbols, the one that probably has the greatest historical footprint among the population. Even so, like almost any subject susceptible to generating passions and dislikes, it is not exempt from criticism and polarized opinions.

The exacerbation and overexposure of national symbols during dictatorial periods (Primo de Rivera's regime, Francoism) had an effect contrary to the intended one, generating disaffection among a large part of the population. This was especially notable in territories with a marked alternative identity sentiment, which, over time, would translate into the strengthening of their own symbols and institutions as a means of channeling an autochthonous nationalism to counteract the centralist oppressor, thus legitimizing their refractory or disruptive role.

It is precisely in these territories where the greatest rejection of the flag is shown, as attested by the war of the flags (more pronounced years ago; somewhat less today): a set of incidents ranging from flag burning to the non-compliance with the Law 39/1981, mentioned several times in this article, which mandates the presence of the Spanish flag in public buildings. Similarly, in non-strictly institutional settings (civil society, media), the use of the flag is minimal, if not nonexistent.

From a framework not necessarily linked to nationalist circles, there is a segment of the population that, as a consequence of the historical episodes noted above, brands the flag as Francoist. It is not uncommon for a certain percentage of people with this perception to even believe that the flag was created by Franco. Similarly, those who perceive themselves ideologically as republicans or, simply, anti-monarchists, repudiate the flag for considering it monarchist; for them, the tricolor flag of the Second Republic represents a break with a form of government or state they disapprove of.

Likewise, it is worth noting the so-called appropriation of the flag by the political spectrum generally encompassing the right and the far-right—that is, the partisan use and abuse of the ensign in an attempt to capitalize on it, which evokes reminiscences, precisely, of the aforementioned dictatorial periods.

Ultimately, in no few occasions, the flag is observed through different ideological or subjective prisms that burden it with a certain particular connotation, making it perceived as alien or hostile.

The characteristic 1:2:1 proportion of the stripes on the Spanish flag is known in vexillology as Spanish fess, for being the most recognized among those that feature this configuration, just as occurs for flags with vertical stripes with the flag of Canada, whose pattern is known as Canadian pale. These terms are sometimes applied even if the canonical proportion is not strictly met. Examples of flags with the Spanish fess are those of Cambodia or Lebanon.

In the scope of Armed Forces personnel, the oath or promise before the Spanish flag is conceived as a prerequisite for acquiring the status of a professional soldier, in accordance with the provisions established in Law 17/1999, of May 18. It is a public and solemn act in which military personnel express the acceptance of a formula, stated by the authority presiding over the act, which includes a series of patriotic and constitutional commitments; subsequently, they individually kiss the flag and collectively parade under it and, occasionally, the saber of the referred authority. Finally, the soldier's decalogue is recited, as a set of principles or values that guide the conduct of a military in service, or the characteristic hymn of the corps or unit.

For its part, the civilian population, in accordance with the provisions indicated in Order DEF/1445/2004, of May 16 and subsequent modifications thereof, can likewise adhere to this commitment to the aforementioned values, upon prior request to the corresponding Delegation, Sub-delegation or Defense Attaché's Office. The required prerequisites are Spanish nationality and legal age.

According to the repealed Order DEF/1756/2016, of October 28, the nationality patch displayed on the left sleeve of the Armed Forces' uniforms, where applicable, was defined as a textile rectangle of 56×26 millimeters, with the colors of the national flag. Since the entry into force of Order DEF/114/2025, of January 28, which approves the Armed Forces Uniformity Regulations, the patch now consists of a rectangle of 67×37 millimeters, with the colors of the national flag and an incorporated coat of arms.

The use of the flag, or other national symbols, that requires prior authorization (such as, for example, when it is intended to form part of trademarks or insignia), is the responsibility of the Ministry of the Presidency.

Aside from the term rojigualda, whose origin was discussed in previous sections, there are other nicknames for the flag, generally somewhat derogatory in nature. In Catalonia, it is sometimes called estanquera (tobacconist) because, years ago, the signs or posters of these establishments were usually adorned with red, yellow, and red stripes. On the other hand, in the Basque Country, it is known as piperpoto, which translates roughly to pepper jar/can, since, decades ago, a certain brand of canned peppers (also tomatoes, etc.) used the red-and-yellow colors on their packaging.

Similarly to what happens in other countries in the construction sector (with denominations like Richtfest in Germany, etc.), upon the completion of the structure of a building or a work in general, it is customary to carry out the placement of the flag, that is, to place a Spanish flag on the highest part of the work (sometimes accompanied by the regional one, or sometimes just the latter), as a symbolic milestone indicating the culmination of an important part of the project's execution. It is usually celebrated with some kind of feast in which the workers participate. Also called coronation, this ritual may consist of placing other elements, such as branches, trees, ribbons, etc., instead of the flag.